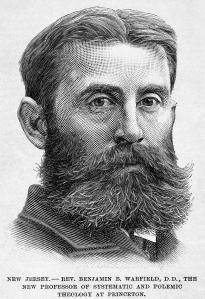

The following selection is the Reformed Position held by B.B. Warfield, published in chapter 14 of Studies in Theology titled The Development of the Doctrine of Infant Salvation

The following selection is the Reformed Position held by B.B. Warfield, published in chapter 14 of Studies in Theology titled The Development of the Doctrine of Infant Salvation

THE REFORMED DOCTRINE

6. It was among the Reformed alone that the newly recovered Scriptural apprehension of the Church to which the promises were given, as essentially not an externally organized body but the people of God, membership in which is mediated not by the external act of baptism but by the internal regeneration of the Holy Spirit, bore its full fruit in rectifying the doctrine of the application of redemption. This great truth was taught alike by both branches of Protestantism, but it was limited in its application in the one line of teaching by a very high doctrine of the means of grace, while in the other it became itself constitutive of the doctrine of the means of grace. Not a few Reformed theologians, even outside the Church of England, no doubt also held a high doctrine of the means; of whom Peter Jurieu may be taken as a type. But this was not characteristic of the Reformed churches, the distinguishing doctrine of which rather by suspending salvation on membership in the invisible instead of in the visible Church, transformed baptism from a necessity into a duty, and left men dependent for salvation on nothing but the infinite love and free grace of God. In this view the absolutely free and loving election of God alone is determinative of the saved; so that how many and who they are is known absolutely to God alone, and to us only so far forth as it may be inferred from the marks and signs of election revealed to us in the Word. Faith and its fruits are the chief signs in the case of adults, and he that believes may know that he is of the elect. In the case of infants dying in infancy, birth within the bounds of the covenant is a sure sign, since the promise is “unto us and our children.” But present unbelief is not a sure sign of reprobation in the case of adults, for who knows but that unbelief may yet give place to faith? Nor in the case of infants, dying such, is birth outside the covenant a trustworthy sign of reprobation, for the election of God is free. Accordingly there are many — adults and infants — of whose salvation we may be sure, but of reprobation we cannot be sure; such a judgment is necessarily unsafe even as to adults apparently living in sin, while as to infants who “die and give no sign,” it is presumptuous and rash in the extreme.

The above is practically an outline of the teaching of Zwingli. He himself worked it out in its logical completeness, and taught: 1. That all believers are elect and hence are saved, though we cannot know infallibly who are true believers except in our own case. 2. All children of believers dying in infancy are elect and hence are saved, for this rests on God’s immutable promise. 3. It is probable, from the superabundance of the gift of grace over the offense, that all infants dying such are elect and saved; so that death in infancy is a sign of election; and although this must be left with God, it is certainly rash and even impious to affirm their damnation. 4. All who are saved, whether adult or infant, are saved only by the free grace of God’s election and through the redemption of Christ.

The central principle of Zwingli’s teaching is not only the common possession of all Calvinists, but the essential postulate of their system. They can differ among themselves only in their determination of what the signs of election and reprobation are, and in their interpretation of these signs. On these grounds Calvinists early divided into five classes: 1. From the beginning a few held with Zwingli that death in infancy is a sign of election, and hence that all who die in infancy are the children of God and enter at once into glory. After Zwingli, Bishop Hooper was probably the first to embrace this view. It has more lately become the ruling view, and we may select Augustus Toplady and Robert S. Candlish as its types. The latter, for example, writes: “In many ways, I apprehend, it may be inferred from Scripture that all dying in infancy are elect, and are therefore saved… The whole analogy of the plan of saving mercy seems to favour the same view. And now it may be seen, if I am not greatly mistaken, to be put beyond question by the bare fact that little children die… The death of little children must be held to be one of the fruits of redemption…” 2. At the opposite extreme a very few held that the only sure sign of election is faith with its fruits, and, therefore, we can have no real ground of knowledge concerning the fate of any infant; as, however, God certainly has His elect among them too, each man can cherish the hope that his children are of the elect. Peter Martyr approaches this sadly agnostic position (which was afterward condemned by the Synod of Dort), writing: “Neither am I to be thought to promise salvation to all the children of the faithful which depart without the sacrament, for if I should do so I might be counted rash; I leave them to be judged by the mercy of God, seeing I have no certainty concerning the secret election and predestination; but I only assert that those are truly saved to whom the divine election extends, although baptism does not intervene… Just so, I hope well concerning infants of this kind, because I see them born from faithful parents; and this thing has promises that are uncommon; and although they may not be general, quoad omnes,… yet when I see nothing to the contrary it is right to hope well concerning the salvation of such infants.” The great body of Calvinists, however, previous to the present century, took their position between these extremes. 3. Many held that faith and the promise are sure signs of election, and accordingly all believers and their children are certainly saved; but that the lack of faith and the promise is an equally sure sign of reprobation, so that all the children of unbelievers, dying such, are equally certainly lost. The younger Spanheim, for example, writes: “Confessedly, therefore, original sin is a most just cause of positive reprobation. Hence no one fails to see what we should think concerning the children of pagans dying in their childhood; for unless we acknowledge salvation outside of God’s covenant and Church (like the Pelagians of old, and with them Tertullian, Epiphanius, Clement of Alexandria, of the ancients, and of the moderns, Andradius, Ludovicus Vives, Erasmus, and not a few others, against the whole Bible), and suppose that all the children of the heathen, dying in infancy, are saved, and that it would be a great blessing to them if they should be smothered by the midwives or strangled in the cradle, we should humbly believe that they are justly reprobated by God on account of the corruption (labes) and guilt (reatus) derived to them by natural propagation. Hence, too, Paul testifies (Romans 5:14) that death has passed upon them which s transgression, and distinguishes and separates (1 Corinthians 7:14) the children of the covenanted as holy from the impure children of unbelievers.” 4. More held that faith and the promise are certain signs of election, so that the salvation of believers” children is certain, while the lack of the promise only leaves us in ignorance of God’s purpose; nevertheless that there is good ground for asserting that both election and reprobation have place in this unknown sphere. Accordingly they held that all the infants of believers, dying such, are saved, but that some of the infants of unbelievers, dying such, are lost. Probably no higher expression of this general view can be found than John Owen’s. He argues that there are two ways in which God saves infants: “ (1) by interesting them in the covenant, if their immediate or remote parents have been believers. He is a God of them and of their seed, extending his mercy unto a thousand generations of them that fear him; (2) by his grace of election, which is most free, and not tied to any conditions; by which I make no doubt but God taketh many unto him in Christ whose parents never knew, or had been despisers of, the gospel.” 5. Most Calvinists of the past, however, have simply held that faith and the promise are marks by which we may know assuredly that all those who believe and their children, dying such, are elect and saved, while the absence of sure marks of either election or reprobation in infants, dying such outside the covenant, leaves us without ground for inference concerning them, and they must be left to the judgment of God, which, however hidden from us, is assuredly just and holy and good. This agnostic view of the fate of uncovenanted infants has been held, of course, in conjunction with every degree of hope or the lack of hope concerning them, and thus in the hands of the several theologians it approaches each of the other views, except, of course, the second, which separates itself from the general Calvinistic attitude by allowing a place for reprobation even among believers’ infants, dying such. Petrus de Witte may stand for one example. He says: “We must adore God’s judgments and not curiously inquire into them. Of the children of believers it is not to be doubted but that they shall be saved, inasmuch as they belong unto the covenant. But because we have no promise of the children of unbelievers we leave them to the judgment of God.” Matthew Henry and our own Jonathan Dickinson may also stand as types. It is this cautious, agnostic view which has the best historical right to be called the general Calvinistic one. Van Mastricht correctly says that while the Reformed hold that infants are liable to reprobation, yet “concerning believers’ infants… they judge better things. But unbelievers’ infants, because the Scriptures determine nothing clearly on the subject, they judge should be left to the divine discretion.”

The Reformed Confessions with characteristic caution refrain from all definition of the negative side of the salvation of infants, dying such, and thus confine themselves to emphasizing the gracious doctrine common to the whole body of Reformed thought. The fundamental Reformed doctrine of the Church is nowhere more beautifully stated than in the sixteenth article of the Old Scotch Confession, while the polemical appendix of 1580, in its protest against the errors of “antichrist,” specifically mentions “his cruell judgement againis infants departing without the sacrament: his absolute necessitie of baptisme.” No synod probably ever met which labored under greater temptation to declare that some infants, dying in infancy, are reprobate, than the Synod of Dort. Possibly nearly every member of it held as his private opinion that there are such infants; and the certainly very shrewd but scarcely sincere methods of the Remonstrants in shifting the form in which this question came before the synod were very irritating. But the fathers of Dort, with truly Reformed loyalty to the positive declarations of Scripture, confined themselves to a clear testimony to the positive doctrine of infant salvation and a repudiation of the calumnies of the Remonstrants, without a word of negative inference. “Since we are to judge of the will of God from His Word,” they say, “which testifies that the children of believers are holy, not by nature, but in virtue of the covenant of grace in which they together with their parents are comprehended, godly parents have no reason to doubt of the election and salvation of their children whom it pleaseth God to call out of this life in their infancy” (art. 17). Accordingly they repel in the Conclusion the calumny that the Reformed teach “that many children of the faithful are torn guiltless from their mothers’ breasts and tyrannically plunged into hell.” It is easy to say that nothing is here said of the children of any but the “godly” and of the “faithful”; this is true; and therefore it is not implied (as is so often thoughtlessly asserted) that the contrary of what is here asserted is true of the children of the ungodly; but nothing is taught of them at all. It is more to the purpose to observe that it/s asserted that the children of believers, dying such, are saved; and that this assertion is an inestimable advance on that of the Council of Trent and that of the Augsburg Confession that baptism is necessary to salvation. It is the confessional doctrine of the Reformed churches and of the Reformed churches alone, that all believers’ infants, dying in infancy, are saved.

What has been said of the Synod of Dort may be repeated of the Westminster Assembly. The Westminster divines were generally at one in the matter of infant salvation with the doctors of Dort, but, like them, they refrained from any deliverance as to its negative side. That death in infancy does not prejudice the salvation of God’s elect they asserted in the chapter of their Confession which treats of the application of Christ’s redemption to His people: “All those whom God hath predestined unto life, and those only, he is pleased, in his appointed and accepted time, effectually to call, by his Word and Spirit,… so as they come most freely, being made willing by his grace… Elect infants dying in infancy are regenerated and saved by Christ, through the Spirit who worketh when, and where, and how he pleaseth.” With this declaration of their faith that such of God’s elect as die in infancy are saved by His own mysterious working in their hearts, although incapable of the response of faith, they were content. Whether these elect comprehend all infants, dying such, or some only — whether there is such a class as non-elect infants, dying in infancy, their words neither say nor suggest. No Reformed confession enters into this question; no word is said by any one of them which either asserts or implies either that some infants are reprobated or that all are saved. What has been held in common by the whole body of Reformed theologians on this subject is asserted in these confessions; of what has been disputed among them the confessions are silent. And silence is as favorable to one type as to another.

Although the cautious agnostic position as to the fate of uncovenanted infants dying in infancy may fairly claim to be the historical Calvinistic view, it is perfectly obvious that it is not per se any more Calvinistic than any of the others. The adherents of all types enumerated above are clearly within the limits of the system, and hold with the same firmness to the fundamental position that salvation is suspended on no earthly cause, but ultimately rests on God’s electing grace alone, while our knowledge of who are saved depends on our view of what are the signs of election and of the clearness with which they may be interpreted. As these several types differ only in the replies they offer to the subordinate question, there is no “revolution” involved in passing from one to the other; and as in the lapse of time the balance between them swings this way or that, it can only be truly said that there is advance or retrogression, not in fundamental conception, but in the clearness with which details are read and with which the outline of the doctrine is filled up. In the course of time the agnostic view of the fate of uncovenanted infants, dying such, has given place to an ever growing universality of conviction that these infants too are included in the election of grace; so that to-day few Calvinists can be found who do not hold with Toplady, and Doddridge, and Thomas Scott, and John Newton, and James P. Wilson, and Nathan L. Rice, and Robert J. Breckinridge, and Robert S. Candlish, and Charles Hodge, and the whole body of those of recent years whom the Calvinistic churches delight to honor, that all who die in infancy are the children of God and enter at once into His glory — not because original sin alone is not deserving of eternal punishment (for all are born children of wrath), nor because they are less guilty than others (for relative innocence would merit only relatively light punishment, not freedom from all punishment), nor because they die in infancy (for that they die in infancy is not the cause but the effect of God’s mercy toward them), but simply because God in His infinite love has chosen them in Christ, before the time, effectually to call, by his Word and Spirit,… so as they come most freely, being made willing by his grace… Elect infants dying in infancy are regenerated and saved by Christ, through the Spirit who worketh when, and where, and how he pleaseth.” With this declaration of their faith that such of God’s elect as die in infancy are saved by His own mysterious working in their hearts, although incapable of the response of faith, they were content. Whether these elect comprehend all infants, dying such, or some only — whether there is such a class as non-elect infants, dying in infancy, their words neither say nor suggest. No Reformed confession enters into this question; no word is said by any one of them which either asserts or implies either that some infants are reprobated or that all are saved. What has been held in common by the whole body of Reformed theologians on this subject is asserted in these confessions; of what has been disputed among them the confessions are silent. And silence is as favorable to one type as to another. Although the cautious agnostic position as to the fate of uncovenanted infants dying in infancy may fairly claim to be the historical Calvinistic view, it is perfectly obvious that it is not per se any more Calvinistic than any of the others. The adherents of all types enumerated above are clearly within the limits of the system, and hold with the same firmness to the fundamental position that salvation is suspended on no earthly cause, but ultimately rests on God’s electing grace alone, while our knowledge of who are saved depends on our view of what are the signs of election and of the clearness with which they may be interpreted. As these several types differ only in the replies they offer to the subordinate question, there is no “revolution” involved in passing from one to the other; and as in the lapse of time the balance between them swings this way or that, it can only be truly said that there is advance or retrogression, not in fundamental conception, but in the clearness with which details are read and with which the outline of the doctrine is filled up. In the course of time the agnostic view of the fate of uncovenanted infants, dying such, has given place to an ever growing universality of conviction that these infants too are included in the election of grace; so that to-day few Calvinists can be found who do not hold with Toplady, and Doddridge, and Thomas Scott, and John Newton, and James P. Wilson, and Nathan L. Rice, and Robert J. Breckinridge, and Robert S. Candlish, and Charles Hodge, and the whole body of those of recent years whom the Calvinistic churches delight to honor, that all who die in infancy are the children of God and enter at once into His glory — not because original sin alone is not deserving of eternal punishment (for all are born children of wrath), nor because they are less guilty than others (for relative innocence would merit only relatively light punishment, not freedom from all punishment), nor because they die in infancy (for that they die in infancy is not the cause but the effect of God’s mercy toward them), but simply because God in His infinite love has chosen them in Christ, before the foundation of the world, by a loving foreordination of them unto adoption as sons in Jesus Christ. Thus, as they hold, the Reformed theology has followed the light of the Word until its brightness has illuminated all its corners, and the darkness has fled away.

Sources:

https://ia600506.us.archive.org/3/items/developmentofdo00warf/developmentofdo00warf.pdf

http://www.davidcox.com.mx/library/W/Warfield%20-%20Studies%20in%20Theology.pdf